The last barrier to financial inclusion (Part 1)

This is part one of a two-part series on financial inclusion. Next week, I’m dropping a free e-book called Fckn Money (2024 Edition)—something I wrote during a sabbatical two years ago, when I had too much time and too many thoughts about why money feels so damn complicated.

When the global economy hit pause in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the knee-jerk reaction of most governments was to roll out cash aid.

Here in the Philippines, we put together a decent PHP 200 billion (approx. USD 4 billion) to support about 18 million households. A big chunk of that aid money was funneled through the Department of Social Welfare and Development’s Social Amelioration Program (SAP).

It was a great idea, except for a tiny problem: the government had no cash delivery mechanism.

Then we got a brief

Back then, our agency was running a USAID-funded financial inclusion campaign focused on expanding access to transaction accounts (bank accounts, e-wallets) and addressing cyber-insecurity issues.

When the cash delivery challenge landed on our table as a campaign brief, we suddenly became part of a multi-agency fire drill (because the economy was on fire lol) to help get cash into people’s hands without breaking quarantine and/or the internet.

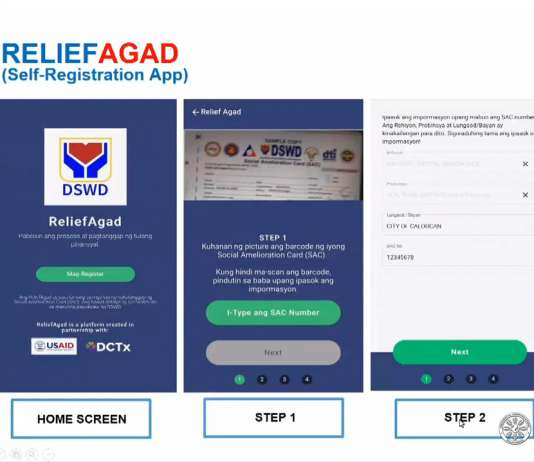

Our delivery machine was called ReliefAgad (which translates to “immediate relief”), something done by the really smart nerds of DEVCON, in partnership with the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT), and USAID.

ReliefAgad worked as an easy-to-deploy platform to collect beneficiary data via barcode or manual entry, then connect that info to e-payment systems like GCash, PayMaya, and bank accounts. Out of 4 million ReliefAgad signups, about 1.2 million people set up transaction accounts to receive their aid money (ayuda).

I thought: well, that was good impact. A clean, measurable number. Fast-forward to 2025 and boy did we see some pretty huge (and honestly, super great) changes:

Connectivity is better. Internet infrastructure is more stable, making it easier to access financial services.

KYC (Know-Your-Customer) is simpler. Banks now only require one ID for setting up new accounts. (Requiring two was a massive barrier to some)

Fintech reach is wide. We clearly have some platform frontrunners. GCash now has around 94 million users. Maya is in the 44–50 million range. Coins.ph has about 18 million. All of which are platforms that offer more than just savings products.

Interoperability is real. Thanks to the National Retail Payment System (NRPS), we can now send and receive money across wallets and banks through InstaPay, PESONet, and—my personal favorite—QR Ph. No more juggling apps, although some banks still charge unreasonable transaction fees, it almost feels like extortion.

Security has improved. OTPs, biometrics, real-time alerts—these are now standard features. Just recently, the Central Bank of the Philippines ordered banks to move away from OTPs in favor of more secure authentication methods.

Financial literacy efforts have multiplied. BSP, banks, and e-wallets all run their financial literacy programs.

Financial products are slowly going mainstream. Insurance, investments, credit, lifestyle bundles—you name it, it’s a tap away. GCash alone reported ₱6 trillion in gross transaction value back in 2022.

Infrastructure-wise, we’ve come a long way. The rails are there, but we know that financial inclusion isn’t just about systems, access, or availability. It’s also about usage and behavior. And culture. And emotion. Despite all this progress, a layer of resistance remains:

The last barrier isn’t tech. It’s us.

Read in full: The Financial Life of Filipinos: Insights into Wealth Distribution and Financial Literacy in the Philippines.

Shame and secrecy (Hiya): We don’t talk about money because we’re embarrassed. Embarrassed to admit we fell for a scam. Embarrassed by how little (or how much) is in our bank account.

Fear of judgment (Mukhang pera): Talking about money feels gross. Wanting more of it feels greedy. So we downplay our ambition (and with it, the means to generate more income).

Conflict avoidance (Pakikisama): We’d rather keep the peace than say no. So we lend money we can’t afford to lose. We bankroll family events with borrowed funds. We avoid conversations that matter.

We don’t talk about money enough. And because of that, we’re missing out on what money is really for.

Now what?

Part 2 comes out next week!